June 2022 update: CISA recently released an alert on the Karakurt extortion group. Read the alert here: https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa22-152a

—

Case Summary

Antigen Security was engaged to assist a victim experiencing a data extortion attempt by a threat group known as Karakurt Team. The week leading up to the attack, MFA logs showed multiple push notifications directed at the victim domain administrator and other AD account holder’s mobile phones with “no response”. The reconnaissance-like behavior culminated in a successful inbound RDP connection directly to the victim’s domain controller/file server using the domain administrator credentials. Antigen assessed that the threat actor successfully bypassed the multifactor authentication process required for remote access using a remote code execution exploit targeting the victim’s SonicWALL VPN appliance’s out-of-date firmware, possibly related to the recent critical vulnerability CVE-2021-20038.

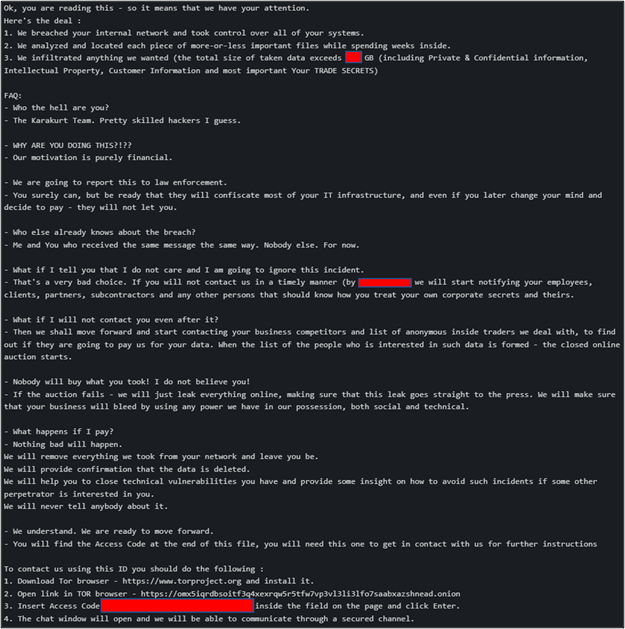

The threat actor occupied the victim network for 5 days before creating numerous notes (see Figure 1 below) on several Windows hosts. Lateral movement occurred primarily via RDP, however in two instances it appeared the actor relied on brute force password guessing. Two pieces of suspicious code, 1.ps1 and sihost.exe, were used by the threat actor periodically during the intrusion. The code could not be collected from the file system therefore the exact function of the code was unknown. Cobalt Strike served as a secondary form command and control method including data exfiltration.

Figure 1: Karakurt Ransom Note

Analyst Comments

Since the Covid-19 pandemic began, there has been a sharp uptick in data extortion attempts with ransom notes but do not necessarily involve encryption or ransomware at all. The note may say something like “pay us or we’ll release your data, tell all your clients, ruin your reputation” etc. In most cases though, it is important to verify the credibility of the ransom letter by reviewing EDR, VPN, MFA, and other log data sources on your network to find out if anything has been exfiltrated, the data asset’s value, and any compliance or regulatory considerations.

Time will tell if data extortion catches on and becomes more effective than traditional encryption-based ransomware. Recently, another ransomware gang called Lapsus$ made headlines when they attempted to extort Nvidia, Ubisoft, and Microsoft. In a heavily regulated industry such as healthcare, financial, legal, data extortion alone might well compel a ransomware victim to pay a ransom. Encrypting data (or whole systems) essential to the victim’s business in the absence of trusted backups, is yet another at least moderately compelling reason to consider paying the ransom. Highly valued intellectual property potentially too. The victim organization did not fit any of the mentioned profiles and not coincidently the data extortion attempt failed. The success of modern data extortion schemes depends on strong upfront open-source intelligence gathering followed by careful targeting choices by threat groups.

Assessing the threat actor’s initial access method was the biggest challenge of the case in part because the little available observed behavior did not match any know behavior to Antigen’s knowledge. Additionally, the victim employed no firewall or network intrusion detection logs to draw from during the investigation. What follows is the circumstantial evidence that went into Antigen’s conclusion. Critical vulnerability CVE-2021-20038 emerged approximately a month ahead of the incident and the victim’s VPN appliance model and software version was confirmed to be affected. Proof-of-concept (POC) exploit code was available at the time of the incident and a separate CVE-2021-20038 RCE was reportedly being used by other threat actors in the weeks leading up to the incident.

The most curious bit of evidence was the victim’s VPN logs themselves. Expected VPN session logs were characterized by logged message details like login/status, duration, and explicitly reflected the business-approved VPN client, NetExtender, in the user-agent string. Conversely, the victim’s VPN logs consistently showed unexpected session information during periods of confirmed intrusion activity that included a user-agent string indicative of the SonicWALL SMA Connect Agent, a related client-side product. The SMA Connect Agent is known to support a “native” RDP client for remote hosts. It was unclear if the unexpected VPN session logs shown below resemble that log behavior. That product was neither distributed nor approved for employee use by the business so there was no log baseline to compare against. MFA was still be expected as part of the authentication process regardless. It is difficult to know exactly what happened with the VPN appliance during the known intrusion sessions without additional research and testing.

![]()

Figure 2: Expected VPN Session Log

![]()

Figure 3: Unexpected VPN Session Log

Lastly, good security awareness for employees was a subtle but critical takeaway from the case. The high number of logged “no response” MFA events were important red flags leading up to the incident. Receiving an MFA push on your cell phone indicates primary authentication succeeded and your credentials are compromised. Whenever that happens it is critical to report the authentication event as ‘unrecognized’ so it can be immediately investigated, and the relevant password changed.

Get Help from Our Experts

As data extortion attacks have become common, it’s important to be prepared with an incident response plan. Antigen Security can help you determine the next steps in the aftermath of an attack. Schedule a meeting with one of our experts to get started.

Suspicious C2 IPs and File Hashes

| IP | Location | ISP Provider |

| 45.134.20.66 | Netherlands | Falco Networks |

| 45.91.21.37 | Netherlands | Panq |

| 193.138.218.161 | Sweden | 31173 Services AB |

| 185.65.50.111 | Latvia | Packethub |

| 185.65.50.106 | Latvia | Packethub |

| 138.99.216.4 | Belize | Life is Good LTD |

| 51.89.190.128 | United Kingdom | OVH |

ps1 (SHA1 – N/A)

exe (SHA1 – 89912ce0489c4040257ea4dad7c8439fcaf32c20)